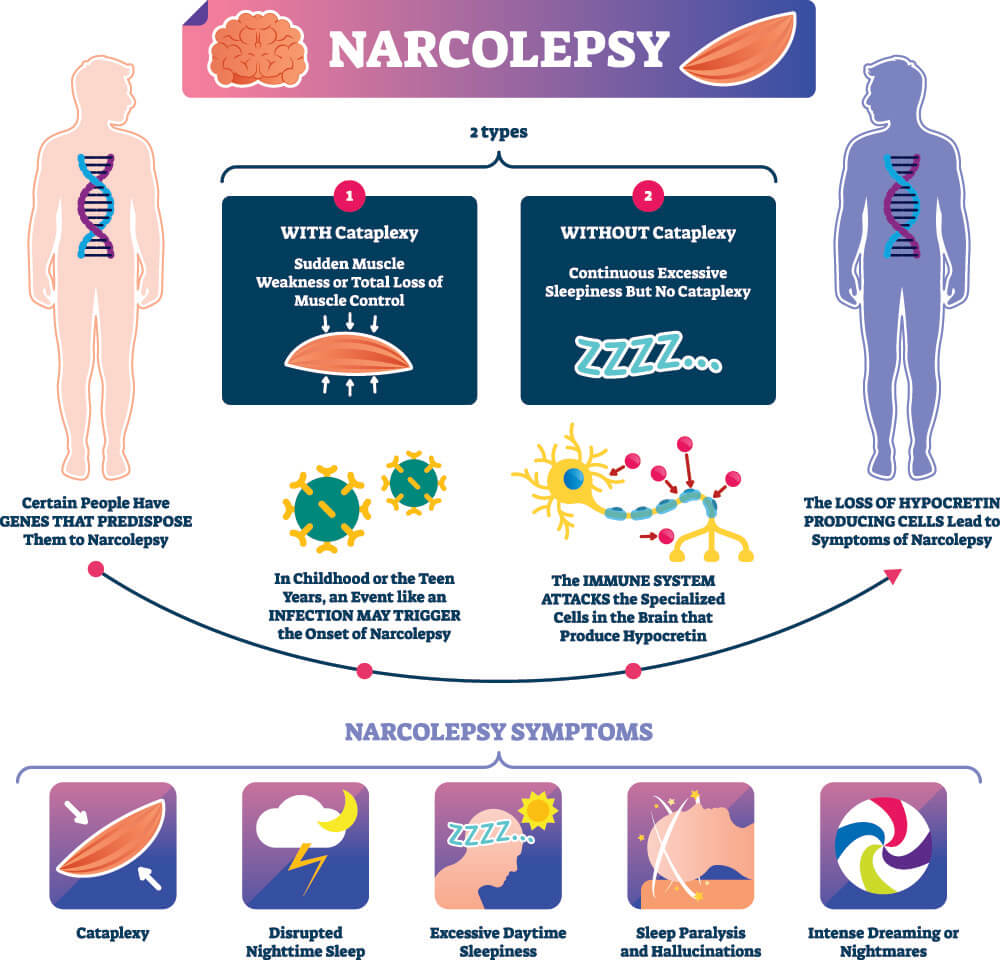

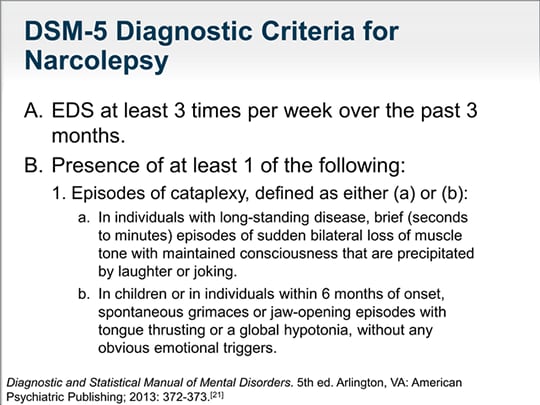

Therefore, cataplexy is believed to represent dissociated REM phenomena intruding into wakefulness after an emotional trigger. The decreased muscle tone observed in cataplexy is similar to the absent electromyographic tone documented during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Hypocretin 1 deficiency appears to play a permissive role, allowing certain emotional states to cause rapid shifts in downstream neurotransmitters, which results in cataplexy. 4 The hypocretin neurons project widely throughout the central nervous system, including the spinal cord. Recently, narcolepsy with cataplexy was associated with a deficiency of the neuropeptide hypocretin 1 (also known as orexin A), which is produced by a small number of cell bodies located only in the lateral hypothalamus. Because of this close association, the pathologic features of narcolepsy provide valuable information about the factors conferring vulnerability to cataplexy. 3 When associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, with or without any other narcolepsy symptoms, cataplexy is considered pathognomonic of narcolepsy. Known primarily as a symptom of the sleep disorder narcolepsy, cataplexy, in extremely rare cases, has been associated with other disorders, which include Nieman-Pick disease type C, Norrie’s disease, mid-brain tumors, and familial isolated cataplexy. Few clinical phenomena better illustrate the ability of an emotional experience to cause neurochemical alterations that result in observable behavioral signs. 2 Consciousness and awareness of the environment are preserved throughout the episode. 1 The clinical manifestations are varied, ranging from involuntary eye closure and neck weakness to a subtle buckling of the knees to generalized muscle weakness that causes the patient to collapse.

In a state of cataplexy, an intense emotional state triggers objective transient muscle weakness verified by areflexia. Cataplexy is one of the most intriguing examples of how thought content can alter neurologic functioning.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)